James Throup, a student from the School of English at the University of

Sheffield, will be spending time in the archives uncovering some of the

fascinating documents which tell the history of Sheffield. In a series of blogs, he will share his

findings…

Over

this coming series of blogs I hope to guide you through a selection of

Sheffield’s rich historical treasures, delving deep into Sheffield Archives and

Local Studies Library to unearth some of the golden relics of the city’s bygone

days. In the process, I aim to show the valuable role such documents play in

our consideration of ideas such as community, identity, social progress, local

heritage, and the lessons that history can teach us.

Over

this coming series of blogs I hope to guide you through a selection of

Sheffield’s rich historical treasures, delving deep into Sheffield Archives and

Local Studies Library to unearth some of the golden relics of the city’s bygone

days. In the process, I aim to show the valuable role such documents play in

our consideration of ideas such as community, identity, social progress, local

heritage, and the lessons that history can teach us.

Our

first journey takes us back to Sheffield in the late nineteenth century, a

period when wages were low, employment was unsecure, and subsequently crime was

rife. Amidst all this, there was a growing fear in Victorian society of a burgeoning

social ‘residuum’ - a class of congenital criminals who were considered beyond

reform.

To

quell such fears, the Habitual Criminals Act of 1869 was passed, followed hotly

by the Prevention of Crimes Act in 1871. These stipulated that repeat

offenders, when released on parole, could be hauled before a magistrate and

made to prove that they were honestly employed. Failure to do so could result

in a further sentence. Additionally, this resulted in the need for a detailed record

of all criminals.

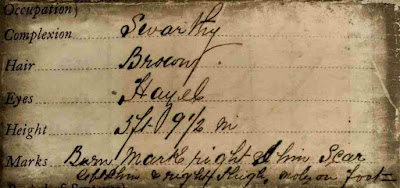

Sheffield

Archives is the proud owner of a ‘Ticket-of-Leave’ book (1864-1874), a ledger

in which the details of each paroled criminal from the Sheffield area was

recorded. In addition to a photograph, each criminal profile features an index

of crime committed, sentence, hair and eye colour, complexion, height, and any

distinguishing marks. In this manner criminals were rendered easier to identify,

and therefore easier to capture if required, but also liable to receive much

harsher sentences for repeat offending. However, some convicts became adept at

circumventing these new modes of surveillance.

One

popular means of evading scrutiny over past crimes was to provide an alias. This

technique is evident in the double entry of George Parker (pages 2 and 132),

aka infamous criminal Charles Peace. Over the course of his criminal career

Peace was guilty of multiple counts of burglary, and eventually hanged in Leeds

in 1879 for committing murder. However, in the entries of the Ticket-of-Leave book,

‘George Parker’ has been convicted for the more prosaic crime of receiving

stolen goods in the first instance, and then burglary with previous conviction

in the second. What I considered most striking about Peace’s first entry is his

photograph. Sat in a wooden chair with his hands clasped in front of him, fingers

entwined, he looks relaxed, as if unconcerned by the proceedings. When Peace

was arrested for the final time in his life, he was not initially recognised

due to the fact that he had disguised himself by shaving the front of his hair

and darkening his skin using walnut juice (Bean 1987: 71). However, suspicions

arose when, as the days in jail passed, the accused man began to change colour.

One

popular means of evading scrutiny over past crimes was to provide an alias. This

technique is evident in the double entry of George Parker (pages 2 and 132),

aka infamous criminal Charles Peace. Over the course of his criminal career

Peace was guilty of multiple counts of burglary, and eventually hanged in Leeds

in 1879 for committing murder. However, in the entries of the Ticket-of-Leave book,

‘George Parker’ has been convicted for the more prosaic crime of receiving

stolen goods in the first instance, and then burglary with previous conviction

in the second. What I considered most striking about Peace’s first entry is his

photograph. Sat in a wooden chair with his hands clasped in front of him, fingers

entwined, he looks relaxed, as if unconcerned by the proceedings. When Peace

was arrested for the final time in his life, he was not initially recognised

due to the fact that he had disguised himself by shaving the front of his hair

and darkening his skin using walnut juice (Bean 1987: 71). However, suspicions

arose when, as the days in jail passed, the accused man began to change colour.

Throughout

the book, I thought it curious that there is a lack of uniform composition

across the various mugshots, indicative, perhaps, of the fledgling nature of

the practice. Some, such as James Horne (page 20), appear as disembodied heads

and shoulders, as if they are lost souls suspended in the ether. Many have

adopted a strong look of defiance, staring straight down the lens with arms

crossed bullishly across their chests, such as William Roebuck (page 143).

Nevertheless, the overwhelming air of these snapshots is one of despair: a

tangible sense of how these people knew they were locked into a system of

little or no work, habitual crime, and then, as a result, increasingly harsher

sentences.

Throughout

the book, I thought it curious that there is a lack of uniform composition

across the various mugshots, indicative, perhaps, of the fledgling nature of

the practice. Some, such as James Horne (page 20), appear as disembodied heads

and shoulders, as if they are lost souls suspended in the ether. Many have

adopted a strong look of defiance, staring straight down the lens with arms

crossed bullishly across their chests, such as William Roebuck (page 143).

Nevertheless, the overwhelming air of these snapshots is one of despair: a

tangible sense of how these people knew they were locked into a system of

little or no work, habitual crime, and then, as a result, increasingly harsher

sentences.

The

vast majority of entries reveal an economic impetus behind the crime committed.

One of the most frequently reported crimes is that of counterfeiting coins.

Crudely cut, ill-weighted coins made counterfeiting an easy crime to detect,

but the sheer number of cases speaks volumes about the economic desperation of

those convicted.

The

Ticket-of-Leave book provides an excellent window into how the Victorian

criminal mind was calibrated, at once rendered more visible and quantifiable,

yet also deemed more incorrigible. Though we may feel we have progressed in our

attitudes from an age where criminality was seen as hereditary, and though

prisoners are no longer subjected to the cruelty of penal servitude, official

statistics for proven re-offenders show that recidivism is slowly rising. Such

artefacts as the Ticket-of-Leave book show how a greater understanding of

punishment and rehabilitation is needed.

James

Throup

‘Ticket-of-Leave

Book (1864 – 1874)’ Sheffield Archives:

SY295/7/3

J.P.

Bean, Crime in Sheffield (Sheffield:

Sheffield City Libraries, 1987) in Local

Studies Library: 364.1 S